Authors: Daniel and Herbert Prince

The Cult

Each year there are numerous seminars promoting expensive rapid microbiology instruments. The instruments discussed offer the supposed advantage of rapid results. However, whether they do offer more meaningful rapid results is very questionable. Is it a measure of Process control/Quality Control? What is clear is that seminars and consultants minimize the facts about how the technology carries with it serious limitations from both a scientific and economic point of view. The new technology requires new, obscure specifications that must be shown to be equivalent to the current microbiology procedures. It advances the use of newly invented technological approaches to promote rapidity. In contrast, traditional Microbiology provides understandable information as to whether living bacteria yeasts and molds are present in pharmaceutical raw materials, finished products, packaging and environments. Classical compendial tests such as USP <51, 61 and 71> unambiguously report whether a living germ is present or not. The reporting can be quantitative such that a raw material is said to have <1 colony forming unit per mL or USP pharmaceutical water is reported to have < 1 CFU/ 100 mL and no Coliforms.

Most of the newly promoted “rapid“ methods do not report whether the organism is or is not alive nor do they provide a sensitive, accurate quantitative estimate of the population of real living cells. Instead they substitute a proprietary technology that targets an attribute (e.g. an inanimate metabolite) that is claimed to be comparable to a living organism. Moreover, it is not revealed how one proves if such an inanimate attribute is equivalent to a classical microbiology plate count. Pseudomonas growth on Cetrimide agar is just one example of a universally accepted living reaction from which the newer technology departs from [See Figure 1] .

Figure 1. Selective Plating as per USP <61>: Pseudomonas aeruginosa has unmistakable appearance and Fruity odor.

For example, if you find remnants of ATP or DNA as proposed as the basis judging the acceptability of the result, is your product adulterated? Does that mean an infectious organism is present? Does that mean that the signal detected is from an organism about which we have limits? This quandry is demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. If you cut out the head off this firefly it still display its luminescence. In some rapid methods this type of artifact will lead to false positive results.

Commonsense and Tradition

These technologies carry price tags from about $50,000 to more than several hundred thousand dollars. All of them require weeks and in some cases years to validate. Usually professional consultants are hired to help write the protocols and oversee the validation effort. This adds considerable expense and leads to the possibility that at the end of the validation one may not be satisfied with the accuracy of the result and conclude that the technology was not validated. Of course there is a very strong bias against letting this outcome happen because of the risk of being associated with an expensive, lengthily failed effort.

The length of time to perform a classical USP test is usually not rate- limiting with respect product release. At the most they take about three to five days—which is enough time for bacteria, yeast and molds to multiply from a single organism into millions of organisms seen as colonies on growth media in petri dishes. Not counting labor the cost of such a test is only a few dollars or so making the classical technology immediately available and much less expensive. Further, one will not have to perform routine and expensive preventive maintenance nor have to revalidate the technology every year or so. In many cases some have learned the hard way that because the “rapid” method was actually slower, more costly, and more difficult to interpret and had a limited throughput that the direct classical traditional method was superior. Common sense tells us that speed is a means to an end and not an end in itself.

Unfortunately, using one of the newer rapid method microbiology technologies usually also locks one into a sole supplier arrangement which may not be worth the risk.

Referring back to USP <61> Microbial Limits test is instructive. Any laboratory from the poorest to richest can perform the same test the same way and report the same result which is specific to critical purpose of the test: are there living organisms present in my sample and if so how many are there? The necessary media, incubators, pipettes, etc to run the tests are available worldwide from numerous ISO certified vendors. When organisms are present there is a need for a confirmatory test for the identification of the organism USP <62>.

Some Rapid Methods Do Offer Advantages Microbial Identification

At Gibraltar we employ rapid microbiology procedures that are the brilliant combination of the efforts of engineers, biochemists and microbiologists. The initial up-front charges are expensive but we believe the expense to be justified because this technology fulfills the critical role for which they are intended. We use the latest in computerized microbial identification analytical instrumentation to harness the speed and accuracy of the miniaturized reactions that have come into prominence in recent years. For example, one of the current generation of instruments employed in our laboratory has increased the accuracy of gram negative identification by a 2-fold factor (48 biochemical reactions versus prior 26) and by at least a 4-fold factor for gram positive cocci (42 reactions versus prior 9). Once in the instrument we can often get the answer as to the genus and species in six hours with a determination estimate of the statistical probability that the identification is correct. And although miniaturized and speedy, the reactivity is classical in nature relying completely on the same physiological parameters required in medical, food and environmental microbiology- as recognized by the American Society for Microbiology and the American Public Health Association. Only with such rapid methodology can a laboratory hope to fulfill the escalating requirements for the identification of microbial content soon to be harmonized [USP <61, 62> and EP <2.6.12, 2.6.13>].

Bacterial Endotoxin

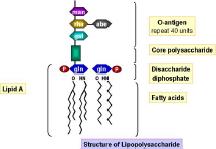

Figure 3: Lipid polysaccharide fever even if its source bacterium is dead. Accordingly, rapid methods are useful to detect the presence of this specific attribute without needing to confirm if the organism is alive or dead.

Another very useful rapid method that we employ is the USP <87> Bacterial endotoxin test as a measure of whether a drug or device can cause a pyrogenic fever response in a patient. This test is a more sensitive, rapid and accurate than the old Rabbit pyrogen test. We know that bacterial endotoxin is the causative agent producing fever. We know its source is predominantly from gram negative bacteria. In this instance what is being directly measured [endotoxin] is the remnant of gram negative bacterial cell wall. No guesswork is needed about what the meaning is of what is being measured. We can confidently set limits [endotoxin units] for the amount of endotoxin such that a patient will be safely treated. In this instance the detection of cell associated material [e.g. endotoxin] is similar in principle to some of the new “rapid” techniques. But the endpoints are different. One advises that a patient may undergo circulatory collapse and the other provides controversy.

An Opportunity for Perspective

Unfortunately few consultants are promoting the classical, traditional microbiology tests that have successfully helped the world wide healthcare system protect patients and consumers for many years. Microbiologists who perform these tests are educated and skilled practitioners who recognize organisms and artifacts. However, the next generation of microbiologist, if only exposed to these new instruments, will not really know how to recognize if an organism is present or not. Such practitioners must properly be referred to as analysts but we are not confident that we could trustingly think of them as knowledgeable microbiologists charged with safeguarding our health. Rather we can refer to them as members of the tabula rasa school of microbiology, a school of science where one may not have benefited by either experience or knowledge.

Webster: “Tabula Rasa, n> L: The mind before outside impressions or experience have affected it; a clean or empty slate.”